This is not a comprehensive analysis of urban developments, but rather a, very western biased, overview of the last 2000 years of urban development, probably part of a longer series of deep dives on the topic.

Urban Beginnings in Classical Antiquity (1st Millennium BCE)

The first major urban centers arose in the 1st millennium BCE in Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and China. Cities like Rome, Alexandria, Chang’an and Pataliputra became hubs of political power, commerce, and culture. As Rome grew into an imperial capital, a sophisticated administrative and legal framework was established to manage the city. Roman rulers implemented structural reforms that facilitated urban expansion, such as standardizing weights, measures and coinage to support trade within and between cities. Legal codes like the Twelve Tables established guidelines for city administration, construction, commerce, and civic duties.

Economically, Roman cities relied on tax collection from citizens and plunder from military conquests to fund infrastructure projects. Major amenities took shape to support growing populations like aqueducts bringing in clean water, sewage and drainage systems, amphitheaters for entertainment, public baths, and grand temples and palaces. The Pax Romana period of the 1st and 2nd centuries CE saw increased stability across the Roman Empire and intensified urban development.

The grid pattern in urban design, often associated with military camp towns, was widely adopted across various cities during a specific historical period. This pattern can be traced back to the standard Roman city plan, which was founded on a system of orthogonal streets, meaning they were laid out at right angles to each other. This highly organized and functional design was not purely Roman innovation, however.

The roots of the grid pattern can be found in ancient Greek city models, particularly those described by Hippodamus, who is often referred to as the “Father of Urban Planning.” He was a Greek architect, urban planner, and philosopher who lived in the 5th century BCE. Hippodamus is best known for his work in the design of the city of Miletus, where he applied a strict grid pattern. His concepts were revolutionary at the time and were seen as emblematic of democratic ideals, symbolizing equality by assigning each citizen an equal portion of space.

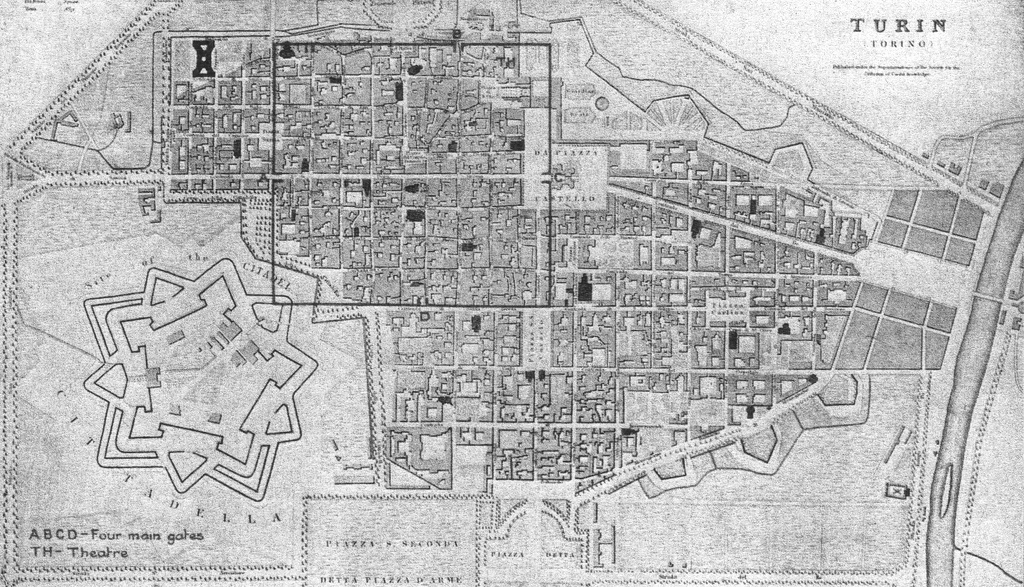

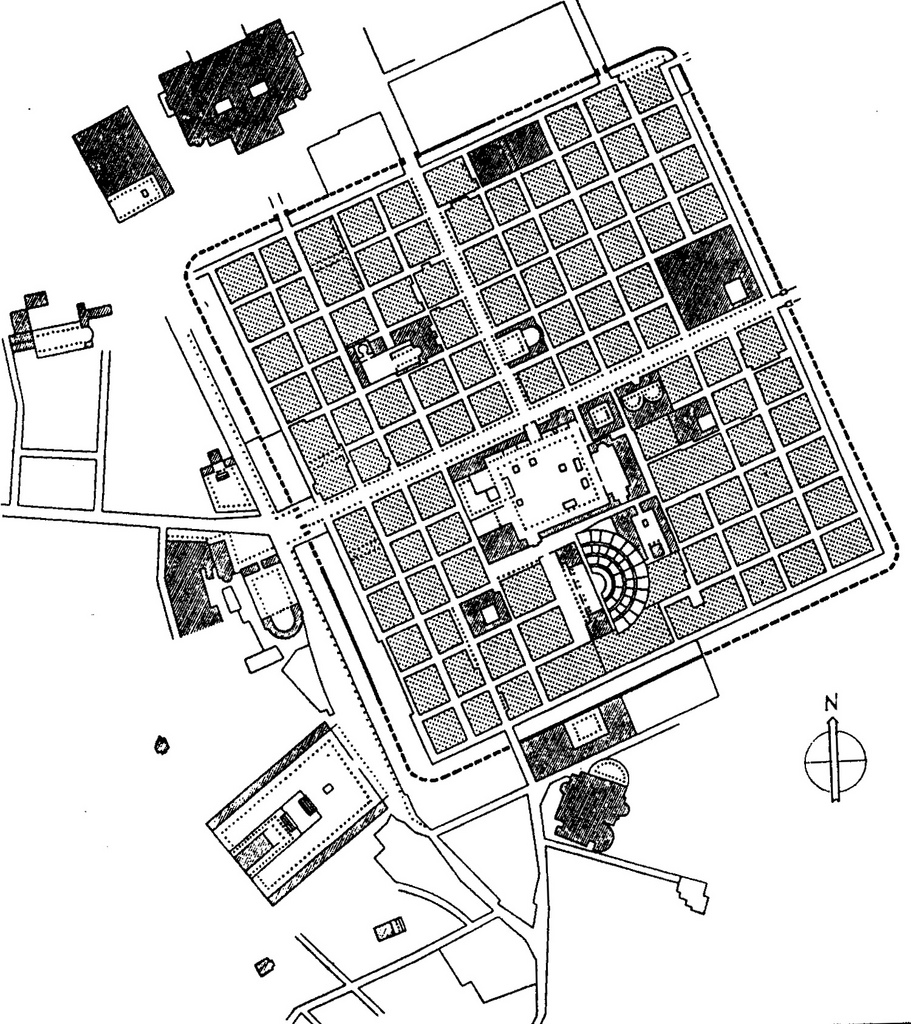

The old Roman city layout in Turin (Italy) is still visible in this map

The Romans saw value in this structured approach and adapted the grid pattern in their military camps, known as “castra.” The design allowed for efficient movement and organization within the camp. This design was then replicated in various Roman cities, such as Pompeii, providing a consistent and easily recognizable urban structure. The combination of straight streets intersecting at right angles allowed for easy navigation and division of land, reflecting a sense of order and discipline that was key to Roman societal structure.

The city of Timgad in Algeria is a classical example of a Roman colonial gridiron town, generated in the context and needs of an orderly military organization.

This grid pattern has had a lasting influence on urban design and can be seen in various modern cities today.

The Spread of Cities in the Medieval Period (5th to 15th Century)

After the fall of Rome around the 5th century CE, urban areas declined dramatically across Europe. However, the emergence of feudalism, a growing monetary economy, expanded trade networks and the rise of Christianity set the stage for towns and cities to flourish again. Beginning in the 10th and 11th centuries, medieval cities like Paris, London, Florence, Bruges and Cologne began growing in population and importance.

Unlike the rational planned cities of the Roman era, medieval cities developed more organically over time, often centered around churches, fortifications, castles, and waterways. Walled medieval cities had twisting narrow streets and very high density. As commerce expanded, guilds became powerful urban actors that regulated trade. Donations from nobles, bishops, and the clergy helped fund the construction of cathedrals, churches, monasteries and other urban infrastructure projects. Taxes on trade and property also provided revenues for city authorities.

Overall, medieval cities had some autonomy to self-govern through councils and appointed officials but remained under the legal authority of monarchies, principalities and the Catholic Church hierarchy. Rulers and nobility granted cities formal charters, allowing them to form guilds, raise taxes, and organize militias in exchange for their loyalty. Yet cities still existed within the broader feudal framework of hierarchy and duty between nobles and vassals.

Urbanization Takes Off in the Industrial Revolution (18th and 19th Century)

Between the mid 18th and 19th centuries, the emergence of modern industry and manufacturing triggered immense urban growth across Europe and North America as people migrated from rural areas into cities seeking jobs in factories and industrial enterprises. Major manufacturing hubs and port cities like Manchester, Birmingham, London, New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Berlin and Hamburg saw massive population booms and unchecked urban expansion.

Industrialization, with its promise of economic growth and advancements in production techniques, drastically altered the urban landscape of many nations during the 19th and early 20th centuries. As factories sprouted in cities, they beckoned thousands from rural areas with the allure of steady employment, resulting in a sudden and often unplanned swell of urban populations. This rapid urbanization, however, wasn’t accompanied by adequate infrastructure development or housing provisions. Cities quickly became overcrowded, leading to the rise of densely packed slums. Living conditions in these areas were deplorable: homes were often makeshift shanties with poor sanitation, and the lack of clean water sources and waste management systems heightened the risk of diseases like cholera and tuberculosis.

Dissent, disorder and debauchery in 18th century Covent Garden | London – William Hogarth

Unlike medieval cities, industrial urban development was fueled by private capital investment and entrepreneurs rather than centrally planned. There were minimal government regulations, zoning laws or interventions at this time to improve living and working conditions.

Nevertheless, grassroots social movements and philanthropic efforts by wealthy reformers gradually helped push political leaders to address the public health crises and inequalities associated with uncontrolled urbanization in this period. Legal reforms like the UK Public Health Acts established sewage systems, housing standards and sanitary codes. Yet unplanned urban development continued creating major issues that cities grappled with for many decades.

20th Century Experiments in Planned Cities

By the late 19th and early 20th century, the chaotic spread of industrial cities combined with dire living conditions for workers created a demand for a more rational, centrally planned approach to urban design and development. Horrified by the congestion, pollution, diseases and inequality pervasive in industrial cities, visionary architects, planners and government leaders began designing planned cities from scratch both in colonies and Western nations.

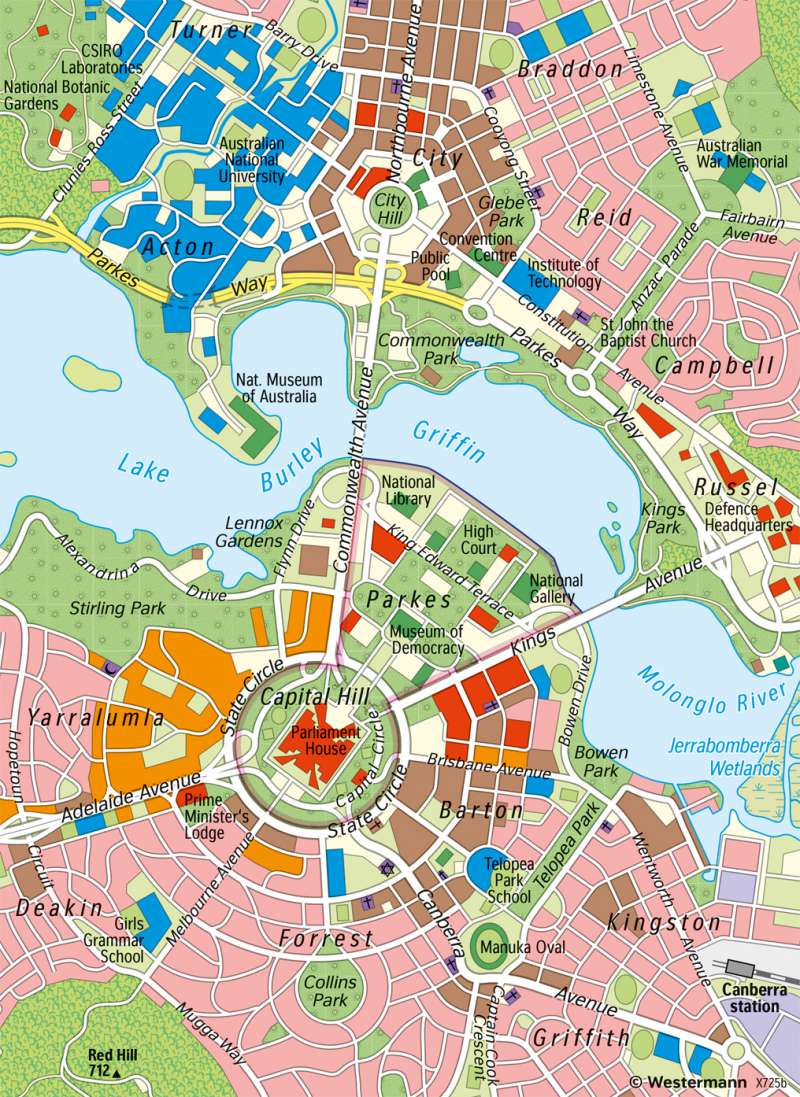

The capital of Australia was a planned city designed by Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. The layout was influenced by the garden city movement and the City Beautiful movement.

Some of the most prominent experiments in planned cities from this era include Canberra, Australia designed to be the administrative capital, or the capital of the Punjab region of India, designed by Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier. Brasília, the iconic capital of Brazil designed by Oscar Niemeyer and urban planner Lúcio Costa in the late 1950s, stands as a testament to Brazil’s aspirations to modernize and stimulate development in the country’s interior. The construction of this city was not merely an architectural marvel but a deliberate and symbolic economic and political undertaking.

The idea behind Brasília was intertwined with then-President Juscelino Kubitschek’s ambitious plan for national development. Coined “50 years of progress in 5”, Kubitschek envisioned rapid economic growth. Brasília was a centerpiece of this vision. By moving the capital from the coast, specifically Rio de Janeiro, to the country’s interior, Kubitschek hoped to diversify Brazil’s economic base and pull economic activity away from the traditionally dominant coastal regions.

Given its centrality to the president’s vision, the Brazilian government channeled significant public funds into Brasília’s construction. This involved not only erecting majestic governmental structures but also laying down extensive infrastructure, creating housing, and establishing other vital facilities. The role of state-owned enterprises in this process was undeniable. These companies, especially those in construction and infrastructure, played a dual role. They served as a conduit for government funding, and they were instrumental in executing the vast construction projects that Brasília’s establishment demanded.

To supplement the substantial government investment, the country sought various financing avenues. Domestic and international loans became critical components of the funding matrix. The ambition behind Brasília’s rapid construction did not come without its economic challenges. The infusion of resources into this project contributed to growing inflation and national debt in the subsequent years.

Additionally, as Brasília took shape and its importance grew, the value of land in and around the city surged. The government astutely leveraged this by selling plots, which in turn became a mechanism to recoup and offset some of the construction costs.

In the annals of urban planning and development, Brasília occupies a special place. Its creation, driven by visionary leadership and facilitated by significant public expenditure, was a monumental task. Yet, beyond its iconic architecture and urban design, Brasília’s story is as much about Brazil’s socio-economic ambitions as it is about bricks and mortar.

Unlike medieval and industrial cities, these were carefully planned from conception with orderly street grids, functional zoning of areas, and ample open parks and public services to improve livability.

This technocratic, centralized planning approach was enabled by national government oversight, public financing and strict zoning regulations. Although constructed to be egalitarian cities, the clean modernist aesthetic and ample amenities were often only accessible to elite governmental workers, excluding marginalized groups. Later critiques emerged arguing that these planned cities lacked the organic vitality and street life of older cities that evolved more incrementally.

Global Cities and Smart Urban Development (21st Century)

While various experiments in centralized planning occurred in the 20th century, a new model of globalized, corporatized urban development has emerged in the 21st century with megaprojects like purpose-built smart cities.

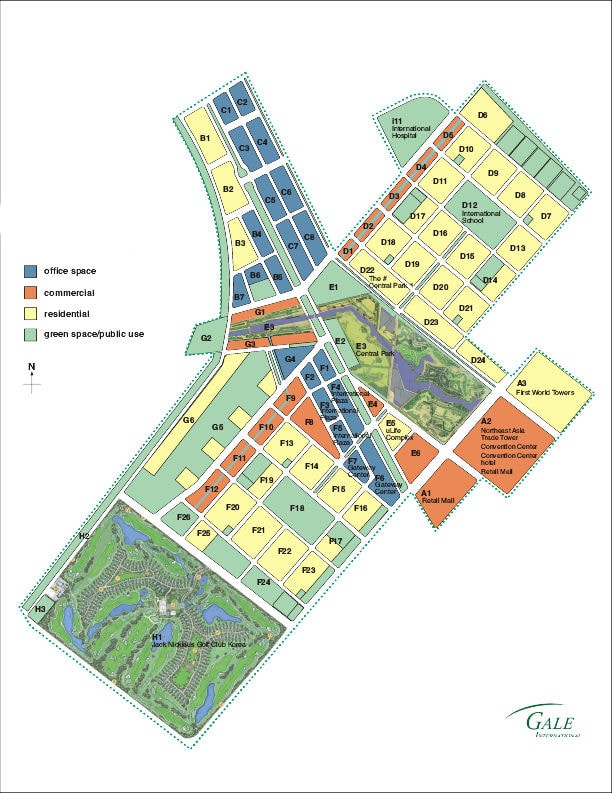

The rise of Songdo in South Korea is often touted as an exemplar of smart city development, embodying a new frontier in urban planning that leverages technology and private investment. Built from scratch on reclaimed land near the city of Incheon, Songdo was ambitiously conceptualized as a “city-in-a-box,” where a single developer could oversee and integrate everything from infrastructure to technology. Designed to be a sustainable, convenient, and highly connected urban environment, the city lured investors with promises of state-of-the-art information technology, green building standards, and comprehensive urban services. Developed as a partnership between the South Korean government and private entities, primarily Gale International and POSCO E&C, Songdo’s rise presented a new paradigm of privately-led, tech-driven urban development that aimed to create an optimized, future-ready city.

Songdo development area circa 2001

Songdo planning layout – Gale 2008

However, the fall or the shortcomings of Songdo offer cautionary tales about the limitations and challenges inherent in such privately developed, tech-centric urban models. For all its smart infrastructure, Songdo has struggled with creating a vibrant community and a sense of place. Critics often describe it as a “ghost city,” with lower-than-expected occupancy rates and public spaces that remain eerily underutilized. There’s also a question about inclusivity and social equity; the high cost of living and focus on attracting international businesses have made it less accessible to average Koreans. Furthermore, the top-down approach to planning and development has resulted in a city that, while technologically advanced, lacks the organic vitality that comes from gradual, community-driven growth. These issues spotlight the complexities involved in creating a city from scratch and raise questions about the viability of replicating the Songdo model in other contexts without significant modifications.

Google Sidewalk Labs was an urban innovation subsidiary of Alphabet Inc., Google’s parent company, founded in 2015 with the goal of reimagining and improving urban life through technology and data-driven solutions. The project aimed to transform a portion of Toronto’s waterfront area, known as Quayside, into a smart city that would showcase various innovations in urban planning, sustainability, and technology integration. The vision included features like self-driving cars, efficient waste management systems, smart infrastructure, and data-driven urban design.

Sidewalk Toronto was a joint effort by Waterfront Toronto and Sidewalk Labs (an Alphabet company) to create a Master Innovation and Development Plan for Quayside – a 12-acre site along Toronto’s eastern waterfront.

Additionally, the project faced regulatory hurdles and public opposition. Community engagement efforts were criticized for lacking transparency and not genuinely reflecting the opinions of local residents. The COVID-19 pandemic further complicated matters, casting doubts on the viability of some proposed innovations in a post-pandemic world.

Amid these controversies and challenges, Google Sidewalk Labs announced in May 2020 that it would no longer pursue the Quayside project. While the initiative aimed to revolutionize urban living through technological advancements, its failure underscores the need for robust public engagement, privacy safeguards, and ethical considerations in the development of smart city projects.

As cities evolve to accommodate rapidly growing populations and complex societal needs, they face a myriad of challenges that technology alone has not yet been able to fully address. Urban areas are struggling with congestion, pollution, housing shortages, and the vast socioeconomic disparities that have become increasingly apparent. While technological advancements promise smart cities with integrated infrastructure and seamless connectivity, there remains a disconnect between technological innovation and practical implementation. Many proposed solutions are either too expensive or complex to be deployed at scale, leaving cities grappling with age-old problems in a futuristic landscape.

The future of cities thus lies in a delicate balance between embracing technological advancements and understanding the underlying human and societal needs that these technologies must serve. Solutions will require not only cutting-edge innovation but also thoughtful integration with existing infrastructure, policies, and cultural norms. Technology must become a tool to augment human capability, not a silver bullet that promises to fix everything overnight. By approaching urban development with a more nuanced perspective that considers the real-world complexities, cities can hope to evolve into sustainable, efficient, and inclusive environments that thrive in the face of future challenges.

Bibliography

Mumford, L. (1961). The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. A seminal text on the evolution of cities from ancient to modern times. Relevant for sections on classical and medieval cities. Didn’t read it all, but great for referencing.

Pirenne, H. (1925). Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade. Princeton University Press. Focuses on the growth of medieval cities and rise of commerce, guilds, and autonomy.

Chapman, S.D. (1971). The Cotton Industry in the Industrial Revolution. Macmillan Education UK. Provides economic analysis of urbanization and industrialization in 18th/19th century England.

Hall, P. (1988). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design in the Twentieth Century. Blackwell Publishers. Traces the history of urban planning ideology and major planned cities of the 20th century.

Scott, A.J. and Storper, M. (2015). The Nature of Cities: The Scope and Limits of Urban Theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 39(1). Contemporary analysis of globalized urban development patterns and theories. Not all necessarily agreeable, but a good starting point.

Datta, A. (2015). New Urban Utopias of Postcolonial India: ‘Entrepreneurial Urbanization’ in Dholera Smart City, Gujarat. Dialogues in Human Geography. 5(1). Didn’t read it all, but offered a good deep dive on the development of Dholera smart city.

Cugurullo, F. (2018). Exposing smart cities and eco-cities: Frankenstein urbanism and the sustainability challenges of the experimental city. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. 50(1). Critical perspective on eco-city and smart city projects and issues.

Carvalho, L. (2015). Smart cities from scratch? A socio-technical perspective. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society. 8(1). Discusses challenges in developing smart cities and need for social lens.

Shin, H.B. (2019). Urban movements and the genealogy of urban rights discourses: the case of urban protesters against redevelopment and displacement in Seoul, South Korea. Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 109(2). Examines conflicts and exclusion in Songdo and Seoul redevelopments.

Angelidou, M. (2014). Smart city policies: A spatial approach. Cities. 41.Provides overview of policies, governance and stakeholders involved in smart cities.

Morris, A.E.J. (1994). History of Urban Form: Before the Industrial Revolutions. Routledge. Provides detailed overview of urban planning and design principles in ancient and medieval cities.

Sjoberg, G. (1965). The Preindustrial City: Past and Present. Free Press. Comparative analysis of ancient/medieval cities and early industrial cities.

Abu-Lughod, J.L. (1999). New York, Chicago, Los Angeles: America’s Global Cities. University of Minnesota Press. Traces economic and demographic evolution of major American cities.

Fainstein, S.S. (2001). The City Builders: Property Development in New York and London, 1980-2000. University Press of Kansas. Examines urban megaprojects and political-economic forces shaping contemporary cities.

Hollands, R.G. (2008). Will the real smart city please stand up? Intelligent, progressive or entrepreneurial? City. 12(3). Key critical perspectives on the concept and discourse around smart cities.

Greenfield, A. (2013). Against the Smart City. Do Projects. Short pamphlet critiquing corporate-led smart city development.

Calvillo, C.F., Halpern, O., LeCavalier, J., Calvillo, N., and Pietsch, W. (2016). Test-Bed Urbanism. Public Culture. 28(2). Analysis of urban “living labs” and implications for democracy and equity.

Certomà, C. (2015). Critical urban gardening as a post-environmentalist practice. Local Environment. 20(10). Discusses urban gardening and agriculture as an alternative approach.